There’s an art to packing a bag for a plein air painting trip. The goal is to keep it light, compact, and practical — bringing only what you’ll truly use.

I usually carry an A5 watercolour pad. It feels less intimidating than a large sheet, and it’s perfect for quick sketches or notes. A pencil and a few pens are essentials for jotting thoughts or adding line work. Then there are the brushes — a small but varied selection — and, of course, the full range of watercolours. You never know which colours will appear once you start observing closely.

The trickiest items to pack are always the jam jar, bottle of water, and ceramic mixing palette. They’re bulky and fragile, but a few wads of tissue help pad and protect them nicely.

Guidebooks recommend visiting Kynance Cove at low tide, when it’s possible to explore the caves and reach Asparagus Island. The descent follows well-kept gravel paths before descending down to the boulders via steep steps. What greets you in this sheltered bay are dark caves and pinnacles of serpentine rocks rising above white sand and turquoise waters.

Cornwall never fails to surprise. This time, the highlight came before the painting even began when I spotted my first family of Choughs, Cornwall’s emblem bird, which are making a slow comeback in the region. With the help of a friendly birder and his binoculars, I caught the flash of their red beaks and legs against the rock. It was a reminder of how the smallest details can hold the day’s true colour.

Choosing where to set up is always part instinct, part pragmatism. Because my aim was to record colour impressions rather than produce a finished composition, I tried not to overthink it. Settling comfortably against a boulder gave me both focus and time, two luxuries when working plein air.

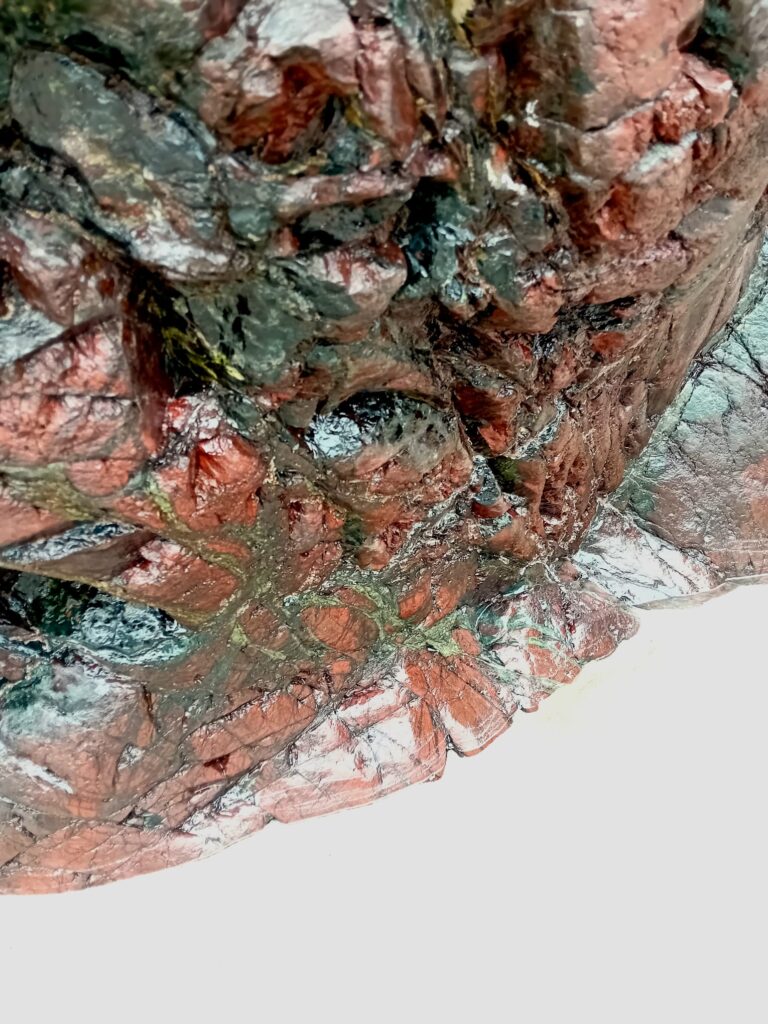

The first revelation was that the serpentine minerals found along this southernmost peninsula of the British Isles aren’t green at all, or not in the way I had expected. There are veins and scales of green deposits, giving rise to its snaky name, but the dominant tones are the dark jasper reds that emerge from granite greys. Still glistening wet from the receding tide, the colours were rich and complex.

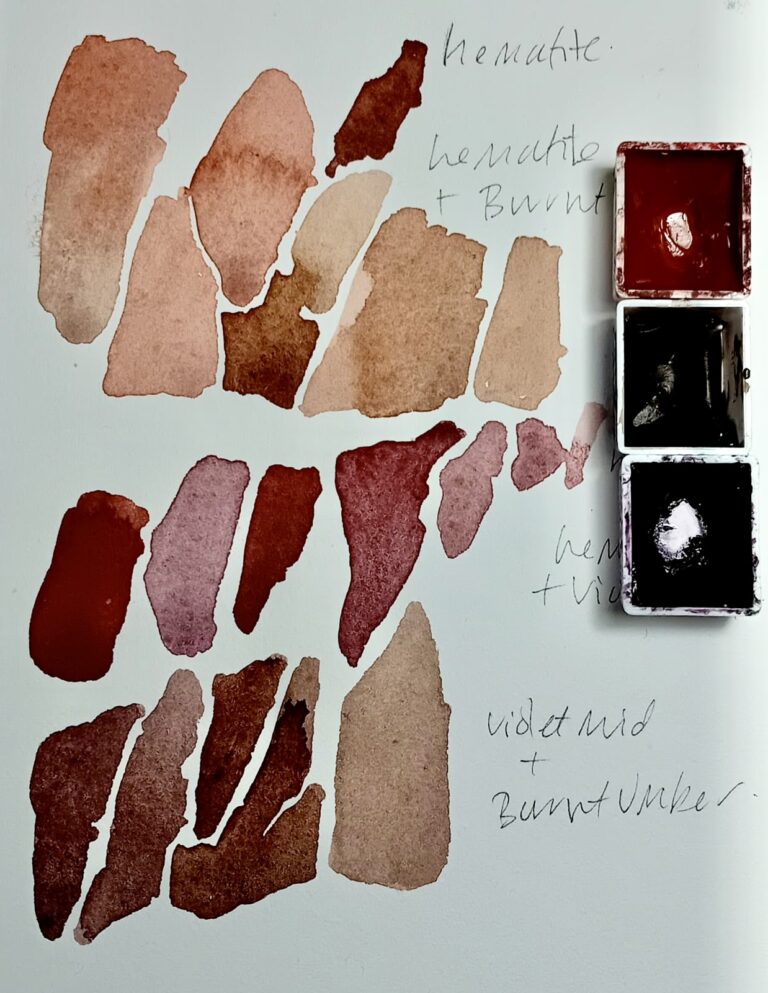

On the palette, I began with Genuine Hematite, a mineral pigment that immediately revealed a deep, reddish-brown warmth. To build stronger earthy tones, I introduced a touch of Burnt Umber, which grounded the mixture beautifully. For added depth and complexity, a little Violet Mid Shade blended into the Hematite brought subtle shifts of shadow and cool undertones.

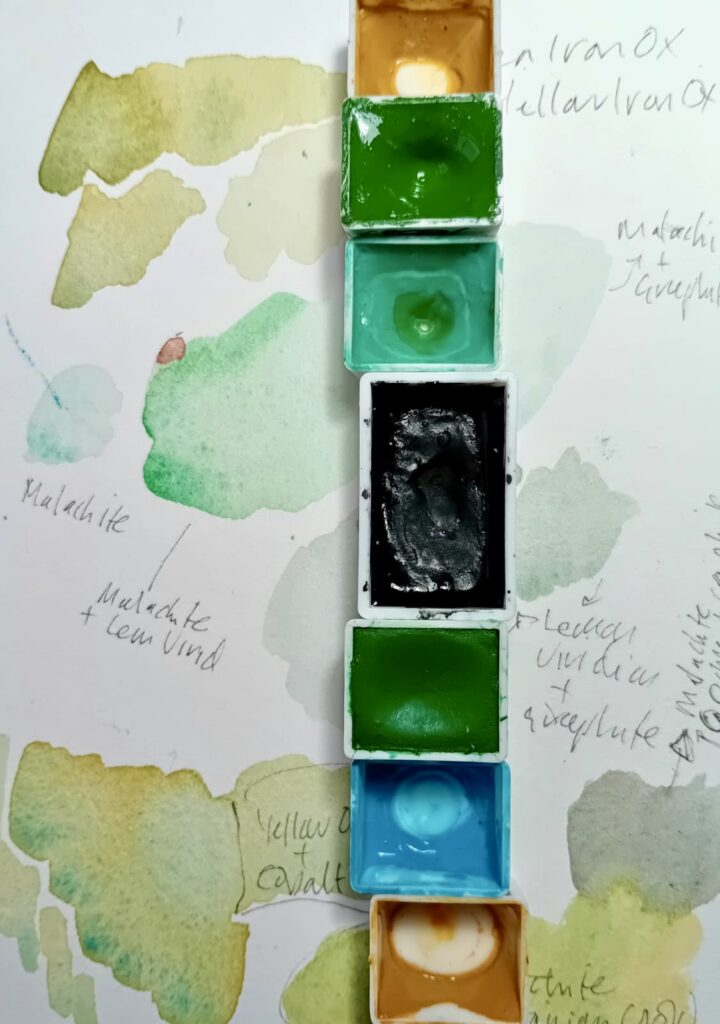

When studying the veins and flecks of green, I turned again to mineral pigments Malachite and Graphite to explore their natural textures. Yet it was the gentle granulation of Cobalt Turquoise, mingling unexpectedly with Yellow Iron Oxide, that brought the greens to life. The resulting hues felt more organic, echoing the layered, living quality of the natural forms I was painting.

Plein air painting, at its best, isn’t about chasing the perfect scene — it’s about learning to see. Packing light, working small, and responding to what’s in front of you allows the experience itself to shape the work. Each trip becomes a conversation between painter and place — and sometimes, the most vivid colours are the ones you discover only by being still long enough to notice them.